Your vanishing health coverage: Employers are cutting retiree health benefits at a rapid rate

Michael Hiltzik - Contact Reporter

May 11, 2016, 10:48 AM - Los Angeles Times

The disappearing benefit: Employers have been cutting out retiree health coverage. (Kaiser Family Foundation)

The shrinkage of employee retirement resources in the U.S. has been well documented, as employers shift more risk onto their workers. Less so is the rate at which employers have been eliminating healthcare benefits for retirees. As the Kaiser Family Foundation recently reported, retiree health coverage is becoming an endangered species.

"Employer-sponsored retiree health coverage once played a key role in supplementing Medicare," observe Tricia Neuman and Anthony Damico of the foundation. "Any way you slice it, this coverage is eroding."

Since 1988, the foundation says, among large firms that offer active workers health coverage, the percentage that also offer retiree health plans has shrunk to 23% in 2015 from 66% in 1988. The decline, which has been steady and almost unbroken, almost certainly reflects the rising cost of healthcare and employers' diminishing sense of responsibility for long-term workers in retirement.

Employer-sponsored retiree health coverage once played a key role in supplementing Medicare. Any way you slice it, this coverage is eroding.

- Kaiser Family Foundation

The implications of this trend hit today's retirees, who typically are eligible for Medicare upon turning 65, right where they live. "The drop in retiree health coverage has important implications for retiring boomers who are approaching their Medicare years with a different set of insurance needs and choices than their parentsf generation," the KFF analysts write.

Financial protection against unexpected healthcare costs is crucial for many Medicare enrollees, especially middle- and low-income members, because the gaps in Medicare can be onerous. The deductible for Medicare Part A, which covers inpatient services, is $1,288 this year, plus a co-pay of $322 per hospital day after 60 days. Part B, which covers outpatient care, has a modest annual deductible of $166 but pays only 80% of approved rates for most services.

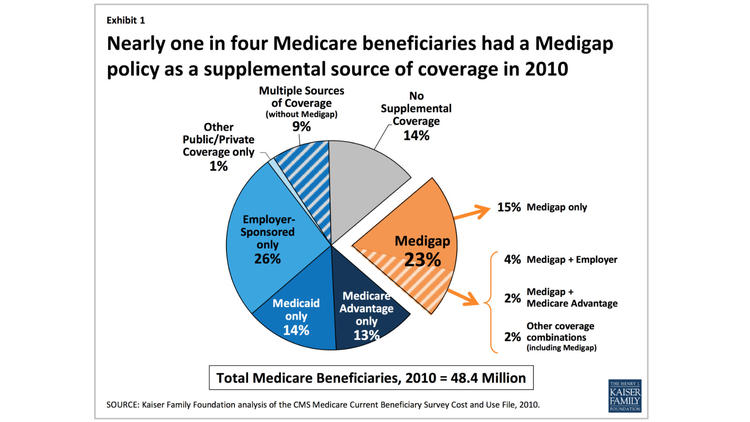

But the consequences of the shift away from employer-sponsored retiree benefits go beyond the rise in costs for the retirees themselves. Many are choosing to purchase Medigap policies, which fill in the gaps caused by Medicare's deductibles, cost-sharing rates and benefit limitations. That has the potential to drive up healthcare costs for the federal government too. That's because Medigap policies tend to encourage more medical consumption by covering the cost-sharing designed to make consumers more discerning about trips to the doctor or clinic. Already, nearly 1 in 4 Medicare enrollees had a Medigap policy — almost as many as had employer-sponsored supplemental coverage.

Nearly as many retirees had Medigap coverage as employer-sponsored health insurance in 2010, but the ratio may be shifting. (KFF)

The trend is sure to fuel interest on Capitol Hill in legislating limits to Medigap plans. Such limits have supporters across the political spectrum: Over the past few years, proposals to prohibit Medigap plans from covering deductibles have come from the left-leaning Center for American Progress, the centrist Brookings Institution and conservatives such as Sens. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Bob Corker (R-Tenn.).

Deprived of supplemental coverage, more Medicare enrollees may opt for Medicare Advantage plans. These resemble HMOs in offering narrower provider networks but annual caps on out-of-pocket spending, unlike traditional Medicare. But Medicare Advantage plans are also more expensive for the government.

The collapse in employer-sponsored retiree coverage hasn't been uniform. Kaiser's employer survey found that among the very largest employers (5,000 employees or more), 42% still offer retiree health benefits; but among those with 200-999 workers, only 20% do. The highest rates of coverage were in finance (49%), state and local government (73%) and communications and utility firms (62%). The rates in the latter two sectors may reflect relatively strong unionization. The lowest rates of retiree coverage appear to be in low-wage sectors such as retail (12%) and agriculture and construction (15%).

The chances of reversing this trend, plainly, are nil. But it's important to keep an eye on it, if only as a reminder that the challenges of federal healthcare policy don't end when Americans age out of the employer and individual markets subject to the Affordable Care Act, and join Medicare at age 65. Limiting healthcare costs for the elderly is certain to become an ever greater concern, as baby boomers age into retirement.